THE MANIPULATION OF TIME.

Keywords: Stagflation, Inflation and recession, boom and bust, business cycles,

Keynes and New Economics, Austrian School, Ludwig von Mises, F. A. Hayek,

Federal Reserve, dual mandate, Great Depression, Great Recession, Obama, F. D.

Roosevelt, manipulation of interest rates and government spending, time

travelling, Ayn Rand, Murray Rothbard,

|

| The Big Bang marked the beginning of time, not the beginning |

A

meditation on the state of the economy’s future by Xuan Quen Santos

“I

AM”

Present tense with no

time before or after; perpetual. Light was separated from darkness. Day and

night, and lights in the sky became signs to mark the seasons, evenings, and

mornings. Time began. Tomorrow became today only to become yesterday. Present

became past. From timeless present to the passing of time with no real present;

ephemeral at best. The patterns of motion seen in the stars, the patterns of ordered

change from darkness to light, and the rhythms and sounds of the rain, the

passing of clouds, and the buzzing of a tiny mosquito are all evidence of the metaphysical

presence of what we call time.

Time

is an essential component of our human experience.

Time is marked with our heartbeats

and our music. It is the one-way path we call life. Time has shaped our

experience and perception. It has shaped our understanding and thinking processes

as it is reflected in the development of language. Mandarin Chinese has no tenses,

and it has to describe any action with its context. Ancient Biblical Hebrew had

only two tenses: completed actions (perfected/past) and actions in process of

becoming past (imperfect/a form of present becoming past). The Greeks conceived

the present as on-going or as continuing. Classic Latin had six tenses with

progressive present. German chopped time in “perfect” parcels without process. More

recent languages have become much more complex in how we describe actions,

motions, processes, and where in time the speaker stands. Spanish has eighteen

verb tenses and English is described by some as having twelve tenses as others

identify sixteen in actual use.

|

| Time has been with us since forever |

The

cognition of the essence of time takes time.

In the Western world, we

expect second graders to begin to grasp time and express it in the conjugation

of at least three tenses: past, present and future. Growing up, it is one of

the difficult hurdles in developing abstract concepts and ordering sequences. Before

then, time is not important other than understanding there are logical

sequences and order of events. This may explain why most children’s stories

begin with a nebulous and imprecise “Once upon a time” and finish with

an equally undefined “Forever after”. Understanding time is difficult for

young children for a number of reasons. Time is an abstract concept, which is elusive

for children to grasp, especially before preschool years. Grasping the meaning

of time as it relates to their experiences reflects directly in their competencies

in language development -oral and written-, math ability, and memory.

|

| Death by plagues, inflation, devaluation, taxes, robbery, corruption, politicians, the FED |

Understanding

the future is the biggest challenge.

The past has already been,

and our memory recalls our experiences. The future does not exist yet; it has

not happened. Imagining the future involves foresight which becomes planning

and preparing. Reasoning about events that could happen or not, mentally

ordering sequences of cause and effect, and picturing ourselves in the future

leads to understanding the distinction between plain human behavior and human

action. This is the difference between organic and purposeful behavior.

Understanding the complexity of the future involves outlining different

possibilities, identifying risks, forecasting results, estimating a duration of

events, and developing a process of evaluating their possible impact on our

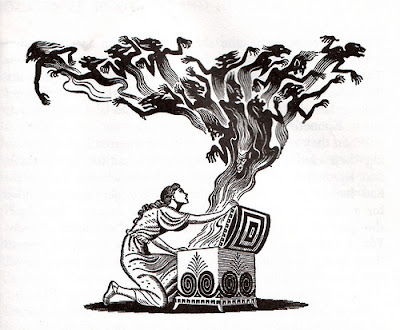

lives. The Greeks used to introduce children into forward thinking with the

story of Prometheus, whose name meant foresight. The careful consideration of

his actions was contrasted with the blunders of Epimetheus, his carefree and impulsive

brother. Pandora with her famous box was sent to confuse them and to disperse

and multiply all the risks and dreadful things that could happen. Developing a

grasp of the concept of the future is an essential category of our humankind.

“Patience

is a virtue” affirms an old proverb.

“Are we there yet?” “Can

I have it now?” (The correct answers are: 1) In 15 long minutes. 2) In a few moments. Children, and many child-like adults, often

struggle to wait for anything, consumed by the immediacy that separates the

present moment from the future. As children progress through elementary school,

this impatience tends to diminish. Understanding the repeating patterns of time

and its measurement units, from seconds to the annual calendar, creates a

degree of comfort in managing time. Adolescence brings with it waves of

impulsive behavior, mood swings and risk-taking tendencies that reflect an

insufficient or defective understanding of the future; that is, a fuller

comprehension of the consequences of their actions. The path to maturity

involves an improving understanding of what the future may bring about and an

adjustment of our own actions to face it. Not all can succeed as adults in

this fundamental task of life. Research shows people with schizophrenia and

severe anxiety disorders can have trouble understanding the relationship

between their actions and their outcomes. People with severe obsessive

disorders can find an impossible feat any necessary changes to adapt to new

circumstances. Most people can navigate the challenges of time and become

better at it by going through what is called “the learning process”. It always

involves review and judgment; that is, a process of selection and

decision-making that involves an evaluation.

|

| A trout in my hook is worth the ten than I could still catch (Think wild turkeys for Thanksgiving! City people don't get it. It is not referring to cute little birds) |

How do we evaluate time

preferences? I have tried the following exercise many times with pre-school

children. I offer chocolates to a child with the following options: I will give

you one piece now, before I tell you a story, but if you listen until we

finish, I will give you two instead. Almost invariably, kids choose one right

away. The smarty-pants will try to negotiate getting the second one at the end

of the story. I have tried to raise the reward for waiting until the end of the

story, but only one was a better negotiator than I. I stopped when the haggling

reached the five pieces I had. I am sure

this child went on to become a financial wizard and a patient listener. Just

like most animals are opportunistic feeders with a wholly uncertain

availability of food, most children will tend towards immediate gratification.

There is something primeval in this pattern. What could be a universal truth is

that if the same reward is offered now or later, without any conditions, all

children would choose instant gratification. The difference in the value of the

extra candy could be considered to represent the value of waiting. If we were

going to get the same reward for waiting and not waiting, we would all choose

not to wait. It is only when the future looks more promising that we will

sacrifice instant gratification for the possibility of a better outcome if we

wait.

Now or

later?

Visualize being offered a

gift of $ 100 today or $ 300 in a month. What goes through your mind? You may

opt for the immediate reward, while others will be patient for some time with

the expectation of the larger sum. These choices are subjective. Some people

will have an inclination or reasons for choosing instant gratification at that

sum. Others may have their own evaluations to justify waiting for the larger

sum. The circumstances and expectations of the future will alter the

evaluations made by different subjects. An uncertain, risky or not promising vision

of the future will elevate the value of present over future, even with a lower

reward. A rosy, almost certain and very attractive expectation will raise the

value of the future, lowering the need for a much higher reward.

What

is on your “bucket list”?

Will your age make a

difference on what you plan? Will your past experiences guide your choices? What

do you believe in? What is important to you? What choices are feasibly

available to you? Would it make a difference if you win big in the lottery? What

if you expect to live 50 more years? What if you are already 50 years old but only

have six months to live? Many years ago, I was travelling to a series of

conferences in Switzerland. While on a long train ride to my destination I met

two old guys from Texas. One was dragging an oxygen tank and had mobility issues

but was still able to walk. His buddy was his age, but he seemed in good

health. Charlie, the first one, was a rancher in West Texas that had just struck

oil. He was also diagnosed with an aggressive terminal illness. Bob, the second one,

was his cousin and guide-assistant on the Grand Tour of Europe they were doing.

I spent the next hours learning about the hard life of ranching in his 10,000

acres of arid lands. I also learned about his plans. He was going to spend as

much as he could of his new fortune and do as many things as possible that he could

not afford before. He was deliberately spending away his fortune in order to

leave the many distant relatives he knew would come after him as little money

and as many problems as he could. They went on with their tour and I never

thought about it until now. A different, between-the-lines bucket list, with a far-view

perspective into the future comes from another ancient Greek proverb I paraphrase, “A

civilization grows great when old grandparents still plant fruit trees in whose

shade they know their still unborn grandchildren will play”. No two persons

are likely to value time and view the future exactly the same way, facing the same circumstance. This

difference is a characteristic of the human social order, but in the absence of

all other considerations, now is always better than a possible, but not

certain, later.

We

all have what has been called “time preferences”.

We

take time into consideration when we make any decision. Absent of all other

considerations, now is always preferred to later. But we may not agree by how much. Now is visible and tangible,

certainty is almost certain, risks are low and seem manageable. Later is only a

possibility that involves many more risks and will cause anxiety. If we are choosing

between present goods and future goods, we always realize that future goods are

still not available, maybe not even in existence.

What

is time?

From Aristotle’s initial thoughts about motion to Einstein’s “thought experiments” comparing moving bicycles and trains that led him to the theory of relativity of time, there is enough serious consideration about the nature of time that a complete library could be filled with the books written about it. There is still no good answer comprehensible in simple terms. A good part of the last hundred years of scientific research has involved the relationship between time and human behavior. Most of it has focused on how our behavior changes from childhood to adulthood. Some studies have even devoted their attention to the effects on the human body of space travel where time in our units of measurement is irrelevant. It was inevitable that foresight and a good deal of imagination would make time a key character in literature. Predictions are a form of seeing the future. In this sense, even the Biblical Prophets were precursor time-travelers, and so was Nostradamus. So were the utopian writers who could foresee a different future. With the appearance of the scientific spirit, Sci-fi has made time traveling a children’s a virtual reality.

|

| "The Time Machine" by H. G. Wells, a Fabian Socialist |

Do

we really comprehend the concept of time?

Even if we don’t have full

cognition of time, we take it for granted as a road through which we must

travel. Literature as such can fill another library with books about time

travel. Many have become movies, and even video-games. A survey will identify

Samuel Madden’s (1733) “Memoirs of the Twentieth Century” as a possible first.

Washington Irving’s (1819) “Rip Van Winkle” may be the first American work of

this nature. The famous “A Christmas Carol” (1843) of Charles Dickens is a

classic. Edward Bellamy, another American, wrote a clearly political promotion of

socialism in his “Looking Backward: 2000–1887” (1887). Mark Twain travelled to

the medieval court of King Arthur (1889). The beginning of the real Sci-Fi

genre began with the classic “The Time Machine” by H. G. Wells (1895), who also

wrote “The War of The Worlds” (1897). Isaac Asimov wrote numerous novels in the

1950s on the topic. Madeleine L’Engle’s “A Wrinkle in Time” (1962) is a much

beloved children’s book, the first of five. Kurt Vonnegut’s “Slaughterhouse-Five”

(1969) has the character randomly jumping from time to time. Christopher Priest’s

“An Infinite Summer” (1976) freezes people in periods of time. “Sphere” (1987)

by Michael Chrichton tells the story of a spacecraft that returns from the

future. The list is long, but skipping two generations we find even the series

of “Captain Underpants” and the series of “Harry Potter” dealing with time

travelling.

|

| "Time Machine", the movie |

In a shorter time, movies are better about time traveling than books.

Movies have become a most

effective vehicle for this type of adventure. Films produced in series, such as

“Back to the Future”, “Planet of the Apes”, “Star Trek” and “Terminator” are

still being shown in the re-runs after many years. I end this list with one more

just to make a point. Harold Ramis’ “Groundhog Day” (1993) has meteorologist

Phil Connors trapped re-living the day of February 2 in Punxsutawney,

Pennsylvania, leading him to re-examine the choices he has made during his past.

If we only could! We always incur a loss of wellness, satisfaction, or benefit

if we do not value adequately what time brings.

|

| Secretary of the Treasury and Chair of the Federal Reserve driving the current stagflation crisis by going Back to the Future |

“Time

is money” is a proverb attributed to Ben Franklin.

The Sage of Philadelphia

published an essay in 1748 titled "Advice to a Young Tradesman".

His advice was simple. Indolence, laziness, not having a job or not producing

anything to trade, costs you money; the money you could have made is your

opportunity cost. Most incomes come from a source of monetary value multiplied

by units of time. Wages are paid by the hour; salaries are bi-weekly or

monthly. Incomes from renting property are paid monthly. Car rentals charge

daily rates. The productivity of labor is always measured by units produced

during a period of time. Productivity increases if more units are produced

during the same period, leading to an increase in salaries. Tools, equipment, and

machinery exist as a product of many people having invested their labor over time

in creating them and making them available. In a way, they have the value of

that time invested ready to be used by someone else. The same concept applies

to a rental home, a VRBO or a hotel room. Even in ancient times, farmers would

pay after the harvest a substantial amount of their crop to the owner of the

land, such as Pharaoh Ramses II. Many British subjects are still paying rent for

his land to King Charles III and his barons. The difference between the earlier

sharecropper contract and the rental or tenancy contract does not change the

time involved as part of the values involved. But there are differences. The sharecropper

serf had to suffer the direction and abuse of the landlord with little

incentives for himself. The tenant or renter had a greater degree of freedom to

direct his “borrowed” land and any excess past covering the rental price was

his. In the first case, his time was owned by the lord. In the second case, he

owned his time. Which system do you think was likely to be more productive?

Are

you paying a mortgage for your house or a note for your car?

If you are a recent buyer,

look at the terms of your contracts and you will find a mortgage or a lien. If

you look at your payment stub in any month, you will find that most of the

money you pay does not go towards buying the house or the car. It goes towards

paying for the time the sellers are giving you to complete paying for what you

bought. It is called paying the interest on the capital. If you stop paying on

time, the house will go back to the bank or to the seller, and the repo truck

will take your car away back to the dealer. Mortgages and liens are legal

mechanisms that protect the property of the lenders in case the borrowers do

not fulfill their promise to pay back. The verb "to borrow" means to receive

something from someone with the understanding of giving it back after a period

of time. What for? The answer is obvious: to use during the agreed period of

time. The reciprocal verb is “to lend”. It means to give for temporary use on

condition that what was borrowed will be returned with the same value. If you

borrow one pound of sugar from your neighbor, you should be prepared to return

no less than the same amount.

Don´t

you hate your neighbor that keeps borrowing your tools but always forgets to

bring them back?

In praxis, there are

three different variants of borrowing that can be recognized in everyday life.

The first is the simple agreement of returning the same thing or value that was

initially borrowed within the agreed time. The second one is what people on

good terms and in a personal relationship will do. When the same thing or value

is returned, the borrower recognizes the benefit he has received for no cost to

him and will be at least grateful or will even give back a good-will gift to

the lender. The third is the most interesting situation. Both parties recognize

from the beginning that the use over time of the thing or value has value

itself. The use is the same as time. The opportunity cost that the lender incurs

becomes a benefit transferred to the borrower. Since both parties have

recognized this as a fact, the next stage is recognizing that what has taken

place is a “market negotiation”, a transaction, an exchange that will become a

contract with an agreed price. The price becomes clear with a number when money

is available. In antiquity, this additional payment the borrower pays the

lender for the time he used the thing, or value was called “the increase”. When

money appeared, the Romans were the first to use a new word with the same root

that originated the verb “to use”. Their Latin word used for paying for the use

of borrowed money became “usury”. Literally, it only means paying for the use.

The concept equally applies to non-monetary things, where a different word was

already in use. The word now is “rent”. Both concepts were not understood as equivalent

and the institutions that dealt with them have developed on different paths

over time. In today’s political mob-baiting language, rent is used to attack

the evil landlords. Usury is when the pawn-shop overcharges interest to the neediest.

Rent

controls and anti-usury laws don’t take into account the value of time.

In today’s world we can

recognize that anybody who can afford it can be a landlord as owning property

is a generalized right, and that anybody can borrow money in a competitive

market environment that has promoted the extensive use of credit. Despite the

realities of today´s open and free market economy, the attacks against rent persist

in the laws of rent controls and squatter rights. The medieval laws against

usury have become modern tools to attack the credit programs that are the ones accessible

to those with low credit rating, no credit record, or ruined credit. These anachronisms

should have disappeared with a better understanding of the economic process

that we now have; but they have not. They are still widely used political tools to

bait the mobs. Modern economics

recognizes that the value of time, when it comes as part of the measurement of

the use of a thing of value or money, is an essential part of the contract. If

it refers only to the duration, it is known as “the term”. If it is clearly part

of a price in money for units of time, it is called “interest rate”. In more

general terms, when applicable to the profits (or losses) of any type of

business measured over time, it is called “rate of return”, but it is not an

interest rate.

The

relevance of time as part of human activity is not clear.

Time is recognized as

inherent in life. We become familiar with time and manage it better as we grow old and mature. We can measure its passing in our surrounding. We consider it when we make any

decision. We have a time-preference that is biased towards the present.

Sometimes we wish we could change the past and even imagine traveling through

time. We know it is implicit in how prices are established in the market for

everything we buy, in the salaries and wages we are paid, and in the rents we

pay. It is part of every contract. It has to do with loans and credit. It has

to do with money and what businesses do. It has to do with our personal plans

and dreams. It has to do with the future we want. All these connections are

recognized, but some have become part of the role governments play in the

social order by having taken over the market institution of money and its

operation. The connection of time to the lending and borrowing of money, or

with buying with money on credit, led to the identification of interest and

exchange rates (usury and agio) two millennia ago. Are those the only relevant

aspects of how we value time in our lives? The philosophers that took an

interest in what happens in the market led the way to the study of what today

we call economics. Many insights were unveiled during the recent five centuries,

but the young science of economics is still in disagreement over several

important points. One of them, perhaps the most important, is how we value time

and its implications. Because the study of this topic began when the control of

money-matters had already been taken over by governments, it is immersed in political

considerations and confused with many other functions that may also not belong

under the control of the bureaucratic apparatus of the state. Adam Smith (1776)

timidly began his exploration of the market because he was concerned that the

kings were hampering the creation of wealth by the people with unnecessary

controls and regulations. He discovered the value of the wisdom of common

people exercising their "natural liberty". He initiated the discussions that brought down “mercantilism” and the coveting

of gold. He claimed it was the people that created wealth when they were free

to do it. One of his followers, David Ricardo (1810) was a banker, stockbroker

and politician who developed further the ideas of interest rates as related to

money and central banking. Business profits were declared a reflection of the interest

rates of capital; but later, Marx and his followers (1848 and 1894) declared the profits of capital were the same as the rent of land, and thus a

stolen value of labor, just as interests charged by banks. In Austria, a new

generation of economists had taken a different approach and were studying

“time-preference” from a broader perspective. The works of Eugene Böhm-Bawerk (1898)

introduced the concept and debunked the entire Marxist construct. He argued

that interest is not produced by exploiting labor. Workers would get the whole

of what they helped produce only if their production were instantaneous. But because

production takes time, some of the value of the product that Marx attributed to

workers really goes to finance the use of capital during the time required for

production. On top of this confusion, another problem occupied the political

economists.

The

Business Cycle. Boom and bust. Expansion and recession. Inflation and

unemployment…

Have you heard about “The Great Depression” (Hoover 1929-1933; FDR 1933-1945), (Hoover 1929-1933; FDR 1933-1945), “The first Stagflation” (Carter 1977-1981), or the “Great Recession” (Obama 2008-2009)? You are now in the “Big Stagflation” of Biden. For much of modern history, many nations have been subjected to recurring upswings and crashes in economic activity. Calling them cycles reflects the arrogance of the defenders of New Economics who are always attempting to be viewed as astrophysicists. These events are recurring, but they are all different and non-cyclical, although many commonalities should have oriented better explanations. The National Bureau of Economic Research reported that the U.S. economy between the 1850s and the early 1980s experienced 30 recessions lasting 18 months on average, with intervening periods of economic growth averaging 33 months. These events were declared inherent to capitalism and a symptom of its agony. The “Great Depression” was announced as the “Death of Capitalism” by the populist socialist movements (International socialism, National Socialism, Fabian Socialism) that came to power propelled by the desperation that poverty brings. It was really a reflection of the lack of a theoretical explanation. Some of the discussions have continued, but it is now generally accepted that the cycles are caused precisely by the fixers that blindly manipulate the “time-preference” of the people by playing with interest rates, credit, banking regulation, price controls, inflation and free trade. The answer to the business cycle lies in a better understanding of how we value time and how we manifest it in our actions. The Austrian School, as championed finally by F. A. Hayek, won the debate against Keynes and his New Economics, but that happened only in the last few decades.

Mathematics

added to the confusion.

From what some call

Classic Economics to A. Marshall’s (1890) and I. Fisher’s (1906) influential

contributions, the ideas about the interest rate were tied to money and banking

and some mysterious “rate of profit” (Return on capital) that businesses would

produce much like the old rent, an invariable flow. At that time, the old

landlords had added banking and factories to their portfolios. The old idea

popularized by Marshall, Fisher and many others, was that the rate of interest was

determined by the rate of profit. This would happen by arbitrage between the

rate of profit on production and the rate of profit in banking. This theory was

developed by economist Irving Fisher in "The Theory of Interest, as

Determined by Impatience to Spend Income and Opportunity to Invest It" (1930).

He described interest as the price of time, and "an index of community’s

preference for a dollar of present over a dollar of future income”. More modern

theories about banking and credit argue that in a credit economy, the rate of

profit in banking is the margin between deposit (savings) and lending rates of interest

but have said little about the rate of interest that emerges as a price that

reflects the “time preference” of all the participants in the market, and in

all economic activities besides credit. There

is no necessary connection between the rate of interest and the rate of profit

in the economy. There is no rate of profit. If there is any relationship to interest,

is that profits in any business can be judged as worth the effort, or not, by

comparing what the same invested capital would earn in a long-term bank

deposit.

|

| Economist Phillips and the machine to help the Central Banks (Cambridge) |

Marshall and Fisher, one in England and the other one in the United States, were great teachers with mathematical minds, and they popularized mathematics as an analytic and pedagogic tool in economics. However, both alerted their disciples to the dangers of seeing too much into the formulas they could produce because they could suggest false relationships. Constantly criticized by the scientists of the “pure sciences” for lacking a scientific method, economists with inferiority complex became enamored with mathematics, and smitten with computers since they became available. Computers were supposed to save the socialist planners from failure. Even some Nobel Prizes have been thrown in there supporting the idea. It can´t work. Political economists (Usually work for government agencies) and banking economists (Always work in the sector most regulated by government) invented econometrics, macroeconomics, and economic models (mimics of the market process). Since then, they refer to the market as if it is a machine, with engines, controls, fuel, residues, spare parts, and of course, a machinist: the political economist. Just listen to the members of the Federal Reserve. Their models imply there are no human agents with free wills, dreams and plans; just cogs and wheels and levers.

|

| Where do free people fit here? |

Their

imaginary machine has no room for you.

Have you seen that nine

out of ten times one of those economists is talking, he is explaining why his

plans or predictions did not come true? The creativity and innovation that a

single entrepreneur brings to market is considered a wrench thrown into their

machines that will destroy their beautiful mathematical constructs. I admire

Joseph Schumpeter’s works in economics (1948) but one comment he made

describing innovation in the market tagged him as the father of “the

creative destruction of capitalism”. This has obliterated the fact that he

was just explaining how the market selects the innovations that will succeed:

the factories of horse drawn buggies, most stables, saddle makers, and hay

farmers disappeared as people chose the new automobiles. Critics always forget

that cars brought factories, industrial workers, refineries, mechanics, and gas

stations, among many other innovations, such as collision insurance and

ambulance chasers. Have you paid attention to the current discussions about AI?

Those whose jobs seem at risk, and the mob-baiters, are already opposing change

and asking for regulation and guarantees against change. Some economists even

say that this innovation will generate the next recession. History shows that

when the carriage makers realized the only significant change was getting rid

of the horses, many became the first automakers. Most of the many brands of

the early days of the auto-industry began as carriage or bicycle makers. Do you

know why the power of engines is measured in “horses”? Do you remember the Pony

Express? The telegraph? Marconi? The tickertape? The wall-phone? The Telex?

The fax? How many people still collect postage stamps? E-mail arrived and is

here to stay…or maybe not.

The

disciples ignored their teachers.

The new enthusiasm for

mathematical tools, formulas, statistics, graphs and new hypotheses invaded the

universities and government agencies after the proclaimed “death of capitalism”.

In search of the prestige that the disguise of mathematical methods gave it, the

disciples proclaimed having found the “touchstone” in the new economics. The listed

cause of death of what properly should be called free-market economics had been

the series of “great unemployment and financial crashes” (Also mislabeled “the

business cycle” of boom and bust, or inflation and recession) that had never

been fully explained, beyond the greed of capitalist monopolies. These

recurring events had been tagged as an inherent defect of capitalism. The sequences

of inflation and recession had really been accompanied by the Civil War in the

U. S., and large-scale European wars that plagued the end of the XIX century

and exploded in WW I. During this time, there was persistent manipulation by

governments in the rates of interest, inflation and rates of foreign exchange. A

lack of a consistent explanation, a real theory that could solve the economic

and financial world crisis that became known as “The Great Depression” (1929-1941),

was the nail in the coffin. In the political scene, the death of the Classical

Liberal and Conservative parties had already happened since 1914. Ancient

empires were broken, and the surviving kings were rendered powerless. The new

states resulting from the wars and revolutions opted for the promises of communism

(international socialism), national socialism, and Fabian Socialism with what

was labeled “New Economics”. Typical of confusing times and compromising leaders

and intellectuals, new economics was what is now known as a mixed economy:

socialism hopefully financed by state-controlled capitalism. Socialism fused with

capitalism. Socialism con-fused with capitalism, like oil and water that require

agitation to work for a short time. Confusion, agitation, conflict.

The

father of this new option of economic policies was Lord John Maynard Keynes.

Keynes was the favorite

disciple of Marshall and a great mathematician on his own merit. He became the

leading Fabian Economist of the English Labor Party (Socialist). Public

sentiment depressed and over-anxious because the policies of old economics had

not solved the situation, and afraid of what the National Socialists were doing

in Germany and the communists in the new Soviet Republics, the mild form of

confused socialism was adopted in the UK. Keynes (1936) expanded his influence

in the United States and his ideas became the New Deal. His disciples propelled

the new wave of political economists that flooded the federal government. Two

of them must be highlighted: John Kenneth Galbraith and Paul Samuelson, both of

Harvard. Galbraith was diplomat, political activist and advisor to five

American Presidents and a powerful influence in the formulation of public

policies. Samuelson considered mathematics to be the "natural

language" for economists and was the first American to win the Nobel Prize

in Economics. His books were the most widely used textbooks in economics at the

university level for several generations and a key advisor to Presidents

Kennedy and Johnson. Schumpeter, Keynes, Galbraith and Samuelson never agreed

on an explanation of the business cycle. The rate of interest, according to

Keynes, is a purely monetary phenomenon, a reward for parting with liquidity,

which is determined in the money market by the demand and supply of money.

Keynes’

ideas became law.

The policies and state controls

over the economy advanced by the new economics economists have gradually become

Law. The Federal Reserve mandates reflect clearly their contradictory ideas.

The multitude of public spending programs that create inflation and justified

to “stimulate the economy” have grown exponentially from the New Deal, to Social

Security, Affordable Care Act, Minimum Wage Laws, War on Poverty, The Great

Society, Medicaid, Medicare, Older Americans Act, Green New Deal, Unemployment

Insurance, Workers Compensation, SNAP-Supplemental Nutrition Program, WIC

Nutrition for Women and Children, SIS Supplemental Security Income, Housing

Assistance, Child Nutrition and Head Start in public schools that pays for food

and child care, LIHEAP pays electric bills, PELL Grants for college and college

loans, and the list goes on. Among the more recent ones are OBAMA PHONES, and

now BIDEN HIGH SPEED AFFORDABLE INTERNET and Student Loan Forgiveness. There are also

numerous tax exemptions for lower income voters. There are also numerous equally

inspired programs at the state, county and municipal levels. Many of those

promoted and stimulated from the federal government with the offers of free

money through conditional grants. The U. S. Congress married the government of

the United States to Keynes’ ideas in 1946 with the approval of The Employment

Act. It ordered the Federal Government “to coordinate and utilize all its

plans, functions, and resources for the purpose of creating and maintaining

conditions under which there will be afforded useful employment for those able,

willing and seeking work.” This generated an army of economists constantly

collecting massive amounts of data, processing it, analyzing it, and

proposing policies to comply with the mandate.

One

example of error, failure, and cover-up tells the story of the New Economics.

The example is called “The

Phillips Curve”. It was named after Bill (A. William) Phillips, an economist

from New Zealand that made a career teaching at the London School of Economics,

the epicenter of Fabian Socialism. In 1958 he published a paper reviewing a

century of data co-relating an apparent inverse relationship between

unemployment and inflation. Similar patterns were found in other countries and

in 1960, Paul Samuelson and Robert Solow declared clearly that when inflation

was high, unemployment was low, and vice versa. It follows that if inflation is

rising, employment will be increasing; and, when inflation is decreasing, unemployment

will increase. It is easy to conclude that if unemployment is increasing for

any reason, it will be fixed with increasing inflation (public spending). It

also would seem logical to assume that if inflation is getting out of control,

creating unemployment would be a good measure, so interest rates are raised to

kill businesses. I. Fisher, four decades earlier, had already identified the

appearance of such a coincidence, analyzing unemployment and prices. Policy

makers throughout the world fell in love with the Phillips Curve. There it was!

An easy set of controls. In 1977, the U. S. Congress approved for the Federal

Reserve what is known as its “dual mandate." It has been in the news often

during the last three years. The Federal Reserve is to "promote

effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates". Considering that new economics define the interest

also as a price, the mandate becomes: maximum employment without inflation and

low interest rates. With the magic of illusionists, the government economists

defined that an inflation rate of about 2% per year would be OK, even if it is

not the same stable prices. Likewise, unemployment at a rate of 3.5-4.0 % would be OK,

and the management of the interest rate was left up to the banking interests. Somebody thought unemployment subsidies would be a fair response. The

interest rates are manipulated to accelerate (lower rates) or slowdown (higher

rates) the economy. Clarifying how they came up with these numbers requires a full

course in the new language of macroeconomic aggregates and a Ph. D in advanced

math. It is pure “double-speak”.

|

| How we understand (not!) the Phillips machine of the economy |

Reality

proved the Phillips Curve a hoax or a tremendous error in theory.

What the old economists

predicted began to happen. Stagflation in the 1970s: The U.S. experienced high

inflation and high unemployment simultaneously. It was a clear indication the

curve was not an effective predictive tool or policy instrument. In recent

decades before COVID, the relationship between inflation and unemployment became

less clear. The U.S. saw periods of low unemployment without corresponding high

inflation. And now, in the 2020s Biden period, stagflation has returned. Of

course, the excuses and explanations are abundant and obscure, almost enigmatic.

These points highlight why many economists believe the Phillips curve does not

accurately describe the complex dynamics between inflation, unemployment and

interest rates.

Keyne’s

ideas spread throughout the world.

In many countries, the

legal principles and control instruments of the Federal Reserve of the United

States of America have been copied by central bank systems based on the

distorted and expanded ideas of Keynes. In 1944, he was one of the architects

of the conference of Bretton Woods that led to the creation of the World Bank

and the International Monetary Fund. In 1988, the recently created European

Union created the European Central Bank – ECB, with identical objectives as the

Federal Reserve. We are in the era of inflation, planned and measured or

runaway and uncontrolled. As long as Keynes’ ideas remain in force, the risks

of economic failure are predictable and high. Keynesian macroeconomic tools are

the fashionable monetary and fiscal policies of our times. We are well on the

path to socialist economies all over the world.

A

psychological problem? A monetary and banking problem? A government problem? A

law of nature?

Much like Marshall and Fisher,

most economists working within the English educational establishment considered

the “problem” (a topic of scientific study) of time to be linked to the

interest rates that commonly appear in monetary and banking transactions.

Money, banking, and credit are further complicated by exchange rates (dealing

with foreign currencies), inflation rates (the increase of money in circulation

without an increase in production that cause a general increase in prices), and the belief that all these topics belong

under the spheres of control by central banks and public finance ministries.

Mathematics intruded into this framework and all kinds of connections seemed to

have been discovered. At the same time,

the second half of the XIX century, another science, also considered to be a

“behavioral science” as economics is, was developing in Europe under the label

of psychology. This had a parallel area within the medical sciences in what is

now psychiatry. It was inevitable that from these points of view, how we deal

with time and how it becomes part of our lives was also considered a

psychological phenomenon.

No

theory, only conjectures, false correlations, multiple hypotheses and a lot of

confusion.

Historians identify at

least six different explanations of the “business cycle”, most already

identified in previous lines. To this date, some discussion still exists,

mostly the defenders of the Keynes’ “New Economics” that are in control of the

economic policies in most governments around the world. The old economists (the

classics) intuitively linked the interest rates, banking, rents and profits,

but without a real theory. Their heirs, without a complete picture, defended

the market forces as self-correcting, given the right time. The mathematical

schools provided new methods for a holistic analysis of these events but turned

them into a vision of waves and troughs, cycles and a lot of automaticity with

no room for the agency of the actors of the economy, We the People. Then there

was Marx and the labor agitators that never formulated an integrated

explanation beyond the “greed of the capitalists that rob the laborers of the

value of what they produce that will collapse on its own in the hands of

monopolies". Next, there was what many thought Schumpeter had said about the

“destructive forces of capitalism”, blaming every innovation that was

introduced in the market as the cause of periods of unemployment. IBM came

along and allowed more sophisticated mathematical models and regressions. This

ability generated the Monetarist school, of which Milton Friedman is the better-known

exponent. They hold a “narrow-view” generation of free-market economists that

has grown in prominence in the past decades, obviously tied to the functions of

money. Out of the mathematical approach came who I have called “the Great

Illusionist” of inflation, Lord Keynes. According to him, market forces left

alone are incapable of correcting the downside of the recession. He proposed a

psychological shock of good enthusiasm to a depressed people: “stimulating the

economy with public spending programs”. Keynes, as a well-known Fabian socialist,

supported government intervention through fiscal policy. His proposals were

never intended as a permanent model. His disciples did not get this part of the

message. According to the father of “The New Economics”, “…the short run is

more crucial than the long run because in the long run, we are all dead”.

The

ignored Austrians to the rescue. The WW I generation.

Isolated in Austria that after WW I had become the most shrunken empire, and immersed in severe periods of inflation and recession, the economists of the University of Vienna had continued their research on the “business-cycle”. For decades, they had been arch-rivals of the German universities. Both traditions gave rise to what now is identified as the field of behavioral sciences. German (Wundt and Ebbinghaus) and Austrian scholars (Freud and Adler) gave fame to the new disciplines. In those days, universities still had a universal approach to knowledge (philosophy) and the new ideas flowed horizontally. Most economists were also jurists or philosophers. Economists were historians and politicians. Austria had then a renowned faculty of economics that, until this day, is still not well known in the spheres of the English language. The names of Menger, Böhm-Bawerk, Wieser, and Schumpeter identify the first generation. The second generation is identified with the works of Mises and his student Hayek who have now received a much-deserved recognition after moving to the U. S. after WW II. After all, it was Böhm-Bawerk who debunked in 1898 the Marx-Engels theoretical propositions for socialism shortly after they were published in 1894. His Marxist contemporaries regarded him and the Austrian school as “intellectual enemies”. He was born in Vienna and studied law. After teaching at university and serving in the civil service, he was appointed minister of finance during the years 1895, 1897, and 1900. He left the ministry in 1904 and taught economics at the University of Vienna until his death in 1914. His theories of interest and capital were catalysts in the development of modern economics. He proposed three explanations for “time-preference”. The first one was an application of the idea of “marginal utility” of value applied to time. The Austrian school developed Jevon’s intuition that supports the subjective value explanation which is now an accepted theory. The second was to introduce the “psychological factor” illustrated in the examples I discussed here in previous comments. His third argument has been translated as “the roundabout” explanation. It simply states that production takes time, involves multiple steps that make up the “value-added” which is recognized as the net return to capital. Unfortunately, to most people this English word suggests a merry-go-round, or a traffic circle, which may infinitely go around without getting anywhere. Böhm-Bawerk proposed a wider perspective to analyze how “time-preference” influenced all aspects of human life, which includes interest rates, money matters, profits, value, banking and credit, and all the rabbit holes identified by economists. But a full understanding of the value of value of time goes beyond policy matters.

The

Austrian approach solves the mysteries. The Second Generation, WW I – WW II

Austria

and Vienna had been for centuries the center of Western influence in the world.

Its dynasties and bureaucracies had ruled over an empire spanning four

continents. At the end of WW I, it had been reduced to the smallest country in

central Europe, surrounded by former subject states being absorbed into the Soviet

sphere. The period between the wars saw Vienna transformed into a village of

misery and starvation. Long before WW II

broke and they were invaded by the Nazi regime, all the possible economic

catastrophes had taken place. With a lot of cynicism, some would call it a

living laboratory for economic policies and catastrophes. It was in this

environment that Ludwig von Mises (1881-1973) recognized that economics is part

of a larger science in human action. Mises called it “praxeology”

to be considered as the foundation for all behavioral sciences. In 1926 Mises

founded the Austrian Institute for Business Cycle Research. His most

influential student and research associate, who later developed Mises' business

cycle theories, was Friedrich Hayek (1899-1992). Hayek was the director of the

institute until his departure to England in 1931 to teach at the London School

of Economics. He moved to the University of Chicago in 1950. Hayek received the

Nobel Prize in Economics in 1974. Mises moved to New York in 1940 and conducted

a seminar on Austrian Economics, adjunct to NYU. Both had studied psychology,

had doctoral degrees in Law and in Political science, and wrote profusely with

the wide perspective that their life experience gave them. Mises formalized the

integration of “time-preference” into a general social theory. Hayek expanded

it after becoming familiar with what the mathematical economists had done in

the English sphere, and confronted Keynes in one of the most documented, long

lasting, academic debates yet to be seen. The debate itself has been the

subject of many books, but I find Nicholas Wapshott’s (2011) “Keynes-Hayek: The

Clash That Defined Modern Economics”, a handy and well documented narrative of

the controversy between two giants, even if a bias favoring Keynes’ ideas is

obvious. A more complete description of Hayek’s contributions to the

understanding of the “business cycle” can be found at:

https://mises.org/mises-daily/hayek-business-cycle

Putting aside the technicalities, the battle lines between Keynes (New Economics) and Hayek (Market economics) were drawn. Keynes believed it was the government’s duty to do what it could to make life easier, particularly for the unemployed and the poor. He baptized the tools and wrote the dogma. Remember, they were desperate in the middle of the Great Depression. Hayek, who had devoted years to a formal study of the business cycles since the collapse of the rich and extensive Austrian Empire, which was much worse and prolonged than what Keynes was trying to patch-up, had reached the conclusion that it was the erratic and continuous government interventions that caused the periods of boom and bust. Hayek believed it was useless for governments to interfere with the market forces (the common sense of the people) that are as immutable as natural forces. Hayek demonstrated in his many later publications about the impossibility of having the knowledge of what is happening in the economy which is necessary to formulate any meaningful policy opportunely. Mises had already destroyed the theoretical foundations of socialism by simply pointing out that prices, the information system in the economy, would never arise without individual property rights and the free market exchanges.

The

recent decades. The Dilemma seems solved.

The high-level

controversies that surrounded the initial debates have become water-cooler talk

in the dark corners of the central banks around the world, in the ministries of

public finance, and in a few of the non-Marxist faculty lounges of the schools

that teach New Economics. They know their time is up but are going to hold on

to their unnecessary jobs as long as possible. Mises and Hayek’s theories

through their disciples and colleagues went on to timidly influence President

Eisenhower. After a pause, they became the backbone of President Ronald

Reagan’s and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s revolution. Shortly after, the Berlin Wall

came tumbling down. The Monetarist converts to the Free Market at the

University of Chicago (Milton Friedman and Arnold Harberger) had a vehicle in a

small group of their Latin American students of economists that became known as

“The Chicago Boys” when they transformed the economy of Chile after the

communist regime of Allende was toppled. Many of them became consultants to the

governments in other Latin American countries. Some of those countries began to follow Hayek’s advice to tie their

currencies to a “basket” of stable foreign currencies, or to just adopt what at

that moment was the stable U. S. Dollar. Many countries do so now but are

having second thoughts after the U. S. Dollar seems to be in the path of self-destruction

under the Keynesian New Economics. Hayek’s and Friedman’s policy proposals to

free the markets was heeded by countries like Taiwan, South Korea, and Singapore.

Their spectacular success generated the phrase “The New Asian Tigers”. In only

three generations, these countries raised their populations from abject poverty

to the standards of living of the advanced industrial countries. In 2024, they

are rated now among the top ten countries that enjoy the highest indices of economic

freedom. During the last twenty-five years, the U. S. has dropped in the level

of economic freedom so low that is not even among the top twenty countries.

|

| Milton Friedman and Friedrich A. Hayek Champions of Economic Freedom recognized with Nobel Prizes A mathematical/empirical approach and an a priori/logical approach |

The Austrian School’s ideas are now mainstream and spreading

The technical development

of the free-market policies was advanced by a younger generation of academics

around the world, a process that continues. Better known contributions are

those of Hicks (1967), Haberler (1986), Yaeger (1986), and Hughes (1997). Israel

Kirzner has written extensively on the topic of entrepreneurship. Those who

have read Ayn Rand’s epic novels have also found academic companions in the

many works by Murray N. Rothbard, available from the store at The Mises

Institute. Rand and Rothbard have become icons on their own at a more popular

level. Re-reading Rand’s novels is a must for the current generation. On the

policy level, I recognize the seminal work of successful entrepreneurs, such as

Joseph Coors who funded the launching of The Heritage Foundation in 1973, and

Charles Koch who sponsored The Cato Institute in 1974. At a global level, the

legacy of Antony Fisher of the U. K. is not sufficiently recognized. He began

by establishing in London the Institute of Economic Affairs in 1955 that

became the go-to resource of PM Thatcher. Fisher went far and beyond. After promoting

several institutes in the U. S., he established in 1981what is now the Atlas

Network. Its purpose was to expand the academic ideas and policies that support

liberating the market around the world by locating and organizing, or

supporting, likeminded people. The network today claims 500 associate

institutions working in 100 countries. Excellent sources to learn more about the

controversy over the control of the value of time and how it reflects in the economy

and in our lives can be found at the following institutions: The Foundation for

Economic Education, The Mises Institute, The Liberty Fund, The American

Enterprise Institute, and the Adam Smith Institute.

|

| F. A. Hayek receives the Nobel Prize in 1974 |

A

celebration

This meditation was inspired

by realizing that 2024 marks the 50th Anniversary of Friedrich A.

von Hayek’s Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Science. I was honored to know him.

My next meditation tries

to answer the following question. Why does it matter whether the government

controls the value of time or not? What do you think?

No comments:

Post a Comment